How Robotics Learn to Imagine: World Models and Embodied AI

t’s late at night, and you’re walking through a quiet street. Suddenly, you hear the distant bark of a dog and spot a shadow darting behind a parked car. Instinctively, you pause, your mind racing through possibilities — is it a stray, a person, or just the wind? In that split second, your brain has imagined several futures, helping you decide your next move. But what if you were a robot? Would you have stopped, or walked straight ahead?

How Robotics Learn to Imagine

World Models and Embodied AI

1. Introduction: Can Robots Daydream?

It’s a rainy evening. You’re cycling home when a ball rolls across the road. Instinctively, you slow down. You haven’t seen the child yet, but you already know one is coming.

Here you go, Congratulations you’ve just simulated the future in your head. Now imagine a robot in your place. Would it have stopped in time? Well clearly not!

Robots today can lift, sort, and navigate. They can follow lines, avoid obstacles, and execute commands. But ask them to pause and predict? That’s too much to ask for and way beyond their scope. Most current robots rely on reactive control, with only limited forms of prediction, far from true imagination.

In this piece, we explore two key ideas that are shaping the future of intelligent systems: Embodied AI, where intelligence emerges through physical interaction with the world, and World Models, which allow agents to internally simulate outcomes before taking action. We begin with embodied AI, as it sets the stage for understanding why having a model of the world is not just useful but essential for solving complex real-world tasks.

2. Embodied AI: When Thinking Requires Doing

Have you ever seen someone try to dance after watching one tutorial video? That’s what disembodied AI looks like, great at theory but terrible at real life.

Embodied AI refers to systems where intelligence is deeply rooted in the physical world.

The robot learns not from abstract data alone, but through perception and action. It senses its

environment, interacts with it, and adapts over time. Just like we do.

Imagine a warehouse robot:-

- It sees a package (camera input)

- Plans a path (model-based reasoning)

- Grips and lifts (actuation)

- Avoids obstacles (feedback loops)

- All while continuously adjusting its plan using real time sensory feedback, a hallmark of embodied intelligence.

- Embodied AI systems cover the full loop of perception, planning, and control, grounded in real-world interaction. They use sensors (eg. vision, proprioception) to perceive the environment, apply learned or classical planning methods to make decisions, and execute actions via controllers like PID, MPC, or learned policies from RL. These components are not isolated, they co-adapt as the agent interacts with the world, forming a closed-loop learning system.

Unlike traditional AI systems that operate on symbolic rules or massive internet text,embodied AI agents must learn in physically grounded environments. They don’t just infer, they experience. Interestingly, not all embodiment happens in the real world. Simulated physics environments like MuJoCo and NVIDIA Isaac Gym allow robots to perform thousands of practice trials virtually, enabling agents to refine behaviors before they’re ever deployed. These simulations are where many modern policies are born and tested, often long before they touch real hardware.in the physical world. These simulations are where many modern policies first take shape.

Embodied AI connects sensors, learning, and motion. It goes beyond code running in isolation, it lives, breathes (figuratively), and learns from experience.

If disembodied AI is a chess engine, Embodied AI is a self-learning robot arm trying to actually move a knight. Embodied AI is like teaching a toddler to walk by letting them walk. Disembodied AI is like sending them 10 PDFs about Newtonian mechanics

3. Embodied AI in the Real World

Boston Dynamics’ Atlas and Spot exemplify embodied intelligence:

Take Boston Dynamics, for example. Their humanoid robot Atlas and quadruped Spot demonstrate remarkable low-level control and physical agility. Atlas performs complex parkour routines and dynamic obstacle traversal, while Spot autonomously navigates environments, opens doors, and carries out inspection tasks. These aren’t hardcoded behaviors, they emerge from learned motor control, interaction feedback, and motion planning in real-world environments.

However, embodied AI goes beyond locomotion. For instance, robots like Mobile Manipulators in warehouse settings combine visual perception, object recognition, and task-level planning to grasp, sort, and relocate items in changing conditions.

4. From Doing to Dreaming: Why Robots Need a Mind’s Eye

Embodied AI helps robots learn from interaction. But what happens when the world is too unpredictable, too costly, or too risky to explore blindly?

Here’s the dilemma: Should a robot test every possibility in the real world? Or can it imagine outcomes before it moves?

That brings us to the idea of World Models.

5. World Models: Building a Robot’s Imagination

Close your eyes and imagine this: a coffee mug sitting on a tilted table. You predict it will slide. That’s a mental simulation.

Close your eyes and imagine this: a coffee mug sitting on a tilted table. You predict it will slide. That’s a mental simulation.

World Models let machines do the same. They build compressed internal representations of the environment, often called latent spaces, and use them to predict how the world might evolve. These latent spaces capture only the essential dynamics, stripping away irrelevant noise and redundancy. With this internal model, a robot can simulate how its actions would affect the world, without needing to physically try each one.

This enables not just safer and more data-efficient learning, but also more powerful capabilities like strategic planning, counterfactual reasoning (“What if I do this instead?”), and generalization to new environments. In essence, a world model gives the robot an imagination, a way to rehearse, evaluate, and optimize decisions before they’re ever executed.

6. The Architecture Behind the Imagination

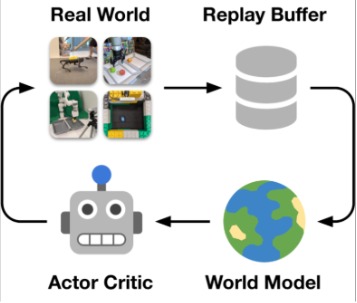

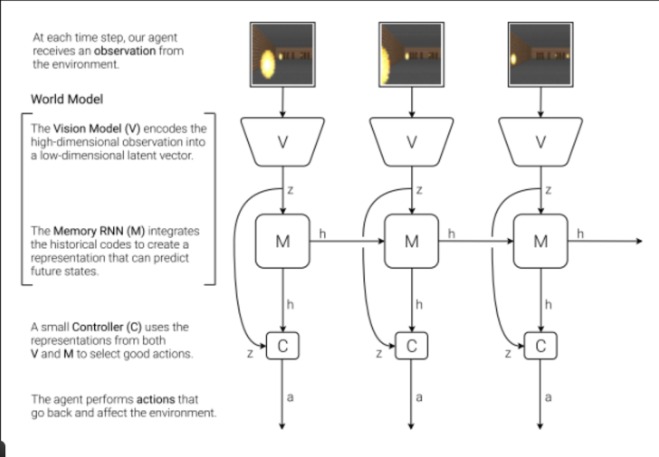

Inspired by the paper World Models by David Ha and J¨urgen Schmidhuber (2018), here’s the general architecture:

- Visual Encoder (V): Compresses high-dimensional input (like camera images) into a compact latent space, often using models like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs). This forms the robot’s internal “mental image” of the world.

- Memory/Transition Model (M): Predicts how latent states evolve over time. Typically implemented using Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) or Recurrent State Space Models (RSSMs), this component acts as the imagination engine, predicting possible futures one frame at a time.

- Controller (C): Uses the predicted latent rollouts to plan or select optimal actions, often via reinforcement learning or gradient-based policy optimization.

This full system allows the agent to perform latent imagination, rehearsing thousands of possible trajectories entirely within its internal model. Trial-and-error doesn’t happen in the messy real world; it happens in the robot’s mind. This makes learning safer, faster, and dramatically more sample-efficient.

This enables internal trial-and-error — learning in imagination, not reality.

7. Why This Changes the Game

World Models let robots:

- Simulate thousands of trajectories quickly

- Avoid crashing during training

- Generalize to unfamiliar scenarios

- Make informed, grounded decisions

It’s like a robot building a mini Bollywood studio in its head and filming futures before acting.” Systems like DreamerV2 showcase how robots can learn motor skills entirely in imagination.

A trained world model lets an agent “look before it leaps.” Instead of blindly trying every possible move, the robot simulates the consequences of actions inside its internal model — choosing only the best ones to execute in reality. Here’s a metaphor from the original World Models project: “World Models is like a robot building a mini Bollywood studio in its head. It shoots films of possible futures, reviews them, and picks the best script to act out.” In real-world robotics, this principle powers systems like DreamerV2, where quadruped robots learn to walk, climb stairs, or recover from slips, not by trial-and-error in the real world, but by imagining outcomes using their learned latent models. This unlocks safe, data-efficient, and highly adaptive behavior with far less physical wear and risk.

8. Why Does It Matter to Us?

World Models unlock a powerful new paradigm: robots that don’t just react, but imagine. They simulate, rehearse, and plan, all inside their learned internal representations. But like all breakthroughs, this too comes with its boundaries. Let’s start with the limitations:

What Holds Us Back?

1. Prediction drift over time

Even small errors in a learned world model can accumulate over multiple imagined steps. This leads to “hallucinated” futures that quickly diverge from reality, a known challenge called compounding error. The longer the agent dreams, the less accurate the dream.

2. The sim-to-real gap

Models often train in simulated environments like MuJoCo or Isaac Gym, which are neat and controlled. But the real world is messy, sensors fail, friction varies, and objects can break. This gap between simulation and reality can be hard to bridge. unexpected edge cases abound. Transferring learned behavior from simulation to physical robots remains a major hurdle.

3. Limited expressiveness in latent space

Most current world models compress reality into a compact latent space, but this comes at a cost. Fine-grained interactions (like finger-object manipulation), 3D geometry, or visual occlusions can be difficult to represent accurately. This bottleneck limits the imagination’s precision.

Where We’re Headed

Despite these challenges, the field is rapidly evolving. Researchers are pushing the boundaries to make robot imagination more accurate, grounded, and useful. Here’s how:

1. Transformers as World Models :

Inspired by advances in language modeling, researchers are now applying Transformer architectures to world modeling. These models, like Recurrent Memory Transformers and Decision Transformers, excel at long-horizon prediction, using attention to preserve context across imagined sequences. Think of it as giving the robot a better memory for the future.

2. 3D-Aware World Models (NeRFs, Gaussian Splatting) :

To imagine in 3D, robots need to go beyond flat latent codes. By integrating tools like Neural Radiance Fields (NeRFs) and Gaussian Splatting, agents can form internal models that understand depth, occlusion, and spatial layout. This opens the door to reasoning about scenes, not just pixels.

3. Curiosity-Driven Imagination :

What if a robot could imagine with a purpose? New approaches link world models with curiosity signals and active learning, encouraging robots to seek out scenarios that challenge their model. In a sense, robots start thinking like scientists: “What happens if I try this unknown thing?”

4. Multimodal Imagination with Language Guidance :

Future world models won’t just simulate dynamics, they’ll do it with intent. By incorporating language-conditioned models, robots can imagine what “put the red block on the green one” looks like, even if they’ve never seen it before. This aligns with research in goal-conditioned world models and vision-language planning.

5. Hierarchical Planning with World Models :

Instead of imagining every tiny joint movement, future systems will reason across multiple levels of abstraction. High-level plans like “make coffee” break down into mid-level goals (“grasp mug”, “press button”), and those break down into low-level actions. This mirrors how humans plan, and it makes imagination scalable.

From Dreams to Decisions

World models are giving robots something extraordinary: a mental workspace, where they can simulate futures, weigh consequences, and act with foresight. But imagination is only as good as the structure behind it. As architectures evolve, so will the quality of the dreams. The future lies in tighter loops between perception, imagination, and action, where robots don’t just move through the world, but think through it first.

10.Conclusion

Back to our rainy road example. The human slowed down not because they were explicitly told to, but because they had a mental model of what could happen next. That internal simulation of the world guided their decision. That’s what world models aim to replicate in machines: the ability to predict, imagine, and plan before acting. It’s not just about being data-efficient or safe, it’s about giving machines the capability to operate intelligently in the real world. Embodied AI is about agents that exist in physical space, interact with objects, and solve real-world tasks. But doing that well isn’t easy. The world is unpredictable, noisy, and filled with complex dynamics. Modeling it, understanding how physical actions lead to outcomes, is incredibly challenging. Today’s models, like V-JEPA.2, show us a glimpse of what’s possible. They try to combine large-scale internet-pretrained knowledge with physical interaction data. The goal is to learn generalizable knowledge that can help robots understand how the world behaves, even in unfamiliar situations. Without such a world model, an agent must learn everything from scratch in the real world, risky, slow, and inefficient. But with one, it can simulate outcomes, plan safely, and act effectively. That’s the core promise: to bridge the gap between raw sensory input and intelligent decision-making. This isn’t just a technical pursuit. If we get this right, it opens up a future where robots can learn, adapt, and collaborate with humans in truly meaningful ways.